Bell’s Palsy: Symptoms, Risks, Diagnosis and Treatment

Schedule an exam

Find Eye DoctorBell’s palsy is a condition in which the facial muscles are temporarily weakened or paralyzed. This may occur due to irritation or pinching of the nerve that controls the facial muscles, or in response to a viral infection. While Bell’s palsy is usually temporary, some symptoms may be permanent.

What is Bell’s palsy?

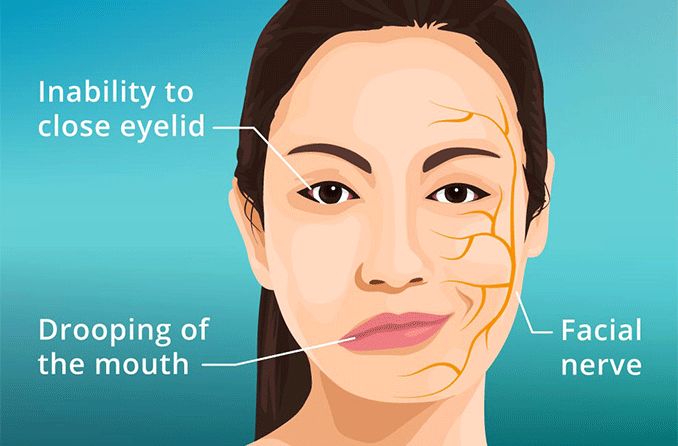

Bell’s palsy — sometimes called “bells palsy” or “facial palsy” — is the temporary paralysis or weakening of the seventh cranial nerve (also called the facial nerve).

The facial nerve extends from the base of the brain to the side of the face, where its fibers branch out and control the muscles of facial expression. Eyelid and forehead movement is also controlled by the facial nerve, as well as taste sensations in certain areas of the tongue.

As a result of the facial nerve paralysis, one side of the face may become stiff or droopy, which is most noticeable when trying to smile. Difficulty closing the eye or raising the eyebrow on the affected side is also common.

Symptoms of Bell’s palsy typically show up suddenly and without warning. Though symptoms range in severity and duration, most cases improve and resolve after a few weeks.

Around 40,000 people in the U.S. experience symptoms of facial palsy every year, with cases being more prevalent between the ages of 15 and 60. The condition affects men and women, as well as various ethnicities, equally.

The name “Bell’s palsy” stems from Charles Bell, a Scottish neurologist who first identified and reported the condition, and palsy, which means paralysis.

SEE RELATED: Third Nerve Palsy

Bell’s palsy symptoms

A telltale sign of Bell’s palsy is drooping of the face and mouth that affects only half of the face. Early symptoms that may indicate the onset of Bell’s palsy are:

Mild fever

Stiffness in the neck

Pain around the jaw or in/behind the ear

Weakness or stiffness on one side of the face

Additional facial palsy symptoms may include:

Inability to control the muscles responsible for facial expressions, such as smiling, raising the eyebrows and blinking, squinting or closing the eyes

Drooling caused by the inability to fully close the mouth

Numbness or loss of feeling in the face

Increased sensitivity to sounds (hyperacusis)

Loss of taste on half of the front part of the tongue

Watering associated with dry eyes, caused by the difficulty or inability to fully close the eyelid on the affected side

Facial symptoms of Bell’s palsy may look similar to those of a stroke. However, Bell’s palsy has no other neurological symptoms and is not life-threatening.

If other stroke-like symptoms accompany your facial droopiness, such as slurred speech, blurred vision and arm weakness, you need to call 911 immediately.

Bell’s palsy symptoms are usually temporary, with many people seeing a significant improvement within three weeks and 85% of people recovering completely within a few months.

SEE RELATED: Is eye twitching a sign of a stroke?

Causes of Bell’s palsy

While the exact cause of Bell’s palsy is unknown, swelling and inflammation of cranial nerve 7 (facial nerve) are usually present in people with symptoms.

Many medical professionals think a viral infection causes the body’s immune system to start targeting the facial nerve, resulting in inflammation and swelling. Viral infections that have been linked to Bell’s palsy symptoms include:

Herpes simplex associated with cold sores and genital herpes

Herpes zoster associated with shingles and chickenpox

The flu virus, specifically influenza B

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Epstein-Barr virus, associated with mononucleosis (mono)

Sarcoidosis, which causes inflammation of various organs

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease

Mumps virus

Rubella, also called German measles

Adenovirus associated with bronchitis, pneumonia and conjunctivitis

Cytomegalovirus infections associated with chickenpox and mono

Cases of facial palsy may also be caused by injury or exposure to dangerous chemicals including dichloromethane.

SEE RELATED: Ramsay Hunt syndrome

Risk factors

People who are at a higher risk of developing facial palsy include:

Those who are pregnant

People with upper respiratory illnesses

Diabetics

People with a family history of Bell’s palsy

Several preexisting conditions raise a person’s likelihood of facial paralysis, such as:

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Diagnosis

There are no specific tests to diagnose Bell’s palsy. It can usually be diagnosed with a physical examination, meaning the doctor can determine a diagnosis by evaluating your physical appearance.

During an exam, your doctor will have you perform different facial tasks, such as smiling, whistling, raising the eyebrows and closing the eyes. While you perform these tasks, the doctor will watch your facial muscles to see if one side is weaker than the other.

To rule out a medical emergency — such as a stroke — your mobility, alertness, speech and other details may be examined.

Preexisting conditions may also be tested to ensure facial palsy is not a symptom of something more serious, including Lyme disease, brain tumor or diabetes. The tests used to accomplish this include:

Electromyography (EMG) provides information on nerve involvement, including if there is any nerve damage, how severe it is and the extent of it.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) ensures your nerves are not being compressed by a brain tumor or bone fracture.

Blood testing can determine whether Lyme disease, diabetes or other preexisting conditions are present.

SEE RELATED: Synkinesis

Bell’s palsy treatment

Symptoms of Bell’s palsy often improve over time without treatment. While facial muscle strength should return to normal after a few months, there are a few things you can do to aid in your recovery, such as:

Apply eye drops regularly in the affected eye to keep the cornea moist and healthy.

Reduce inflammation by taking corticosteroid drugs.

Relieve pain and discomfort with ibuprofen, acetaminophen or other over-the-counter pain medications.

Treat infection with antiviral or antibacterial medication, if it’s determined that a virus or bacteria caused your symptoms.

Wear an eye patch or covering over the affected eye to prevent injury, irritation or drying.

Practice physical therapy exercises to rebuild strength in the facial muscles.

Apply a warm, moist compress to help relieve pain or discomfort in the face.

Stimulate the facial muscles with a facial massage.

If you prefer alternative medicine as a means of Bell’s palsy treatment, you may consider:

Relaxation

Electrical stimulation

Vitamin therapy, using B6, B12 and zinc

Acupuncture

Prognosis

While facial palsy may be a frightening experience, your nerve function will likely return over time. In fact, 85% of people with symptoms of Bell’s palsy will recover within a few months, with children having the highest chance of making a complete recovery.

With this in mind, it’s important to know that the possibility of a full and quick recovery depends on the severity of symptoms and the level of nerve damage. Those who experience complete muscle paralysis will likely have a longer recovery period.

SEE RELATED: Cranial Nerve Palsy

Potential complications

The most common complication of Bell’s palsy has a direct effect on your vision. It’s usually difficult to fully close the eye on the affected side of the face, which can cause the eye to dry out. Excessive dryness in the eye can lead to infection or corneal ulcers, which can threaten your eyesight.

For this reason, it’s important to keep the eye hydrated at night or while looking at a digital screen. Some ways to accomplish this are to use eye drops during the day and ointment or a moisture chamber at bedtime. This helps prevent scratching of the cornea.

If you notice stiffness, tingling or numbness on one side of your face, it’s recommended that you seek medical attention. The sooner you seek medical attention for your Bell’s palsy symptoms, the better your chance is for a quick and full recovery.

READ MORE: What is a neuro-ophthalmologist?

Chris Knobbe, MD also contributed to this article.

Bell’s Palsy Overview. Center for Neurological Treatment & Research. Accessed April 2021.

Bell’s Palsy. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed April 2021.

Bell’s Palsy. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Accessed April 2021.

Bell’s Palsy. Harvard Health Publishing. June 2019.

Bell’s Palsy Fact Sheet. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. October 2020.

Bell’s Palsy. Mayo Clinic. April 2020.

Bell’s Palsy: What Causes It and How Is It Treated? Healthline. August 2017.

Facial nerve palsy after acute exposure to dichloromethane. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. November 2005.

Biofeedback. Harvard Health Publishing. December 2018.

Page published on Monday, March 4, 2019